This post is inspired by an episode of

The Engines of Our Ingenuity, a daily 4 minute radio broadcast produced by the University of Houston's radio station, KUHF. The episode, entitled "

Revisiting Stirrups" explores the notion of the paradigm shift, as first articulated by Thomas Kuhn in his 1962 book,

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. As Dr. Lienhard notes in the episode, Kuhn demonstrated that "science develops, not by

accretion, but by replacement -- by

paradigm replacement." In other words, we can't

make a scientific breakthrough unless we can somehow step out of our

own paradigm and conceive of a new one. Lienhard goes on to talk about

how many have attempted to point out flaws in Kuhn's bold assertions,

but no one has been able to undermine their fundamental validity. In fact, "[a]s Kuhn's detractors

have gone at him, and stripped him of his original

hyperbole, they've left him much stronger." Finally,

Lienhard compares the attacks on Kuhn's work to the criticism levied

against Charles Darwin and the theory of evolution: "I'm astonished by people who try to refute natural

selection by going back to Darwin himself. Never

mind that we've spent a century and a half weaving

the connecting tissue of evolution by natural

selection. You'd think Darwin had written the

last word on the subject, not the

first."

As I listened to this episode, I could not help but think of the

paradigm shift caused in Homeric studies caused by the fieldwork of

Milman Parry and Albert Lord in the former Yugoslavia. Parry's 1928

doctoral dissertation on the traditional epithet in Homer is a brilliant

demonstration of the economy and traditionality of Homeric diction, but

even Parry himself did not grasp the implications of this work

initially:

"My first studies were on the style of

the Homeric poems and led me to understand that so highly formulaic a

style could be only traditional. I failed, however, at the time to

understand as fully as I should have that a style such as that of Homer

must not only be traditional but also must be oral. It was largely due

to the remarks of my teacher (M.) Antoine Meillet that I came to see,

dimly at first, that a true understanding of the Homeric poems could

only come with a full understanding of the nature of oral poetry. It

happened that a week or so before I defended my theses for the doctorate

at the Sorbonne, Professor Mathias Murko of the University of Prague

delivered in Paris the series of conferences which later appeared as his

book La Poésie populaire épique en Yougoslavie au début du XXe siècle.

I had seen the poster for these lectures but at the time I saw in them

no great meaning for myself. However, Professor Murko, doubtless due to

some remark of (M.) Meillet, was present at my soutenance and at that

time M. Meillet as a member of my jury pointed out with his usual ease

and clarity this failing in my two books. It was the writings of

Professor Murko more than those of any other which in the following

years led me to the study of oral poetry in itself and to the heroic

poems of the South Slavs." [The Making of Homeric Verse, 439]

It was only when Parry went to Yugoslavia to observe the still

flourishing South Slavic oral epic song tradition that he came to

understand that Homeric poetry was not only traditional, but

oral—that

is, composed anew every time in performance, by means of a

sophisticated system of traditional phraseology and diction. For Parry,

witnessing the workings of a living oral epic song tradition was a

paradigm shift. Suddenly, by analogy with the South Slavic tradition,

the workings of the Homeric system of composition became clear to him.

Parry planned a series of publications based on his observations

and subsequent analysis of Homeric poetry which were never completed.

His surviving writings have been incredibly influential, but he died at

the age of 33, long before he had a chance to realize the many

implications of his fieldwork. It became the work of his young

undergraduate assistant, Albert Lord, to brings these ideas to the

world.

Albert Lord's

The Singer of Tales, was published in 1960, just two years before Kuhn's

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, but nearly three decades after

his and Parry's initial fieldwork. In the intervening years, Lord not

only went to graduate school and became a scholar in his own right, he

was undergoing his own paradigm shift.

Albert Lord (1912-1991) went to Yugoslavia for the

first time at the age of 22, from June 1934-September 1935. Parry

described his activities as follows:

"…my assistant, Mr. Albert Lord, is shortly leaving for a month in

Greece. His help has been altogether indispensable to me, and I may say

that I have done twice as much work since I had his very able

assistance. He has relieved me altogether of the very long labeling and

cataloguing of the manuscripts and discs, has helped me with the keeping

of accounts and the presentations of reports, has typed some 300 pages

of my commentary on the collected texts, and most particularly he has

ably run the recording apparatus while we are working in the field, this

for the first time leaving me free to be with the singer before the

microphone, and to oversee and take part in the putting of questions to

the singers […] I myself feel the greatest gratitude to him for the help

which he has given me and the expedition is under the greatest

obligation to him." (From M. Parry, “Report on Work in Yugoslavia,

October 20, 1934-March 24, 1935,” Milman Parry Collection of Oral

Literature, p. 12. )

Albert Lord took photographs throughout the trip and kept a record of

his experiences with a view to submitting them to a popular magazine

such as

National Geographic. The essay that he wrote, dated March 1937,

was entitled “Across Montenegro: Searching for Gúsle Songs” and was

never in fact published. We can see already in this early essay a

fascination with two singers in particular that would shape much of

Lord’s subsequent professional scholarship on the the creative process

of oral tradional poetry and the analogy between the South Slavic and

Homeric song traditions. The first is known as Ćor Huso (“Blind Huso”), a

singer of a previous generation who was credited by many of the singers

Parry interviewed as being the teacher of their teacher, and the source

for all the best songs. Lord recounts one of these interviews

(conducted by Nikola Vujnović) as he describes their initial attempts to

find singers in Kolashin:

"In Kolashin we got to work. During the last century this was the home of

one of the greatest singers. The name of old One-eye Huso Husovitch was

a magic one in those days, and still is among the Turks (Moslems) in

the region further east where the old masters of Kolashin now dwell. We

sought eagerly for every trace of his tradition. What was he like? How

did he sing? How did he make his living? How did he die? And so on. We

had heard of him first from Sálih Uglian [sic] in Novi Pazar. From Huso

Salih had learned his favorite song about the taking of Bagdad and its

queen by Djérdjelez Aliya, hero of the Turkish border. In Salih’s own

words, caught by our microphone, we have a bit of the tradition of the

blind singer’s way of life.

Nikola: From whom did you learn your first Bosnian songs?

Salih: I learned Bosnian songs from One-eye Huso Husovitch from Kolashin.

N: Who was he? How did he live? What sort of work did he do?

S: He had no trade, only his horse and his arms, and he wandered

about the world. He had only one eye. His clothes and his arms were of

the finest. And so he wandered from town to town and sang to people to

the gusle.

N: And that’s all he did?

S: He went from kingdom to kingdom and learned and sang.

N: From kingdom to kingdom?

S: He was at Vienna, at Franz’s court.

N: Why did he go there?

S: He happened to go there, and they told him about him, and went

and got him, and he sang to him to the gusle, and King Joseph gave him a

hundred sheep, and a hundred Napoleons as a present.

N: How long did he sing to him to the gusle?

S: A month.

N: So there was Dutchman who liked the gusle that much?

S: You know he wanted to hear such an unusual thing. He had never heard anything like it.

N: All right. And afterwards, when he came back, what did he do with

those sheep? Did he work after that, or did he go on singing to the

gusle?

S: He gave all the sheep to his relatives, and put the money in his purse, and wandered about the world.

N: Was he a good singer?

S: There could not have been a better."

(Trans. by Milman Parry)

Lord later wrote that for Parry Huso came to symbolize “the Yugoslav

traditional singer in much the same way in which Homer was the Greek

singer of tales par excellence.” He continues: “Some of the best poems

collected were from singers who had heard Ćor Huso and had learned from

him” (Lord 1948b:40). Interestingly enough, Parry and Lord do not seem

to have questioned the existence of Huso, though, as John Foley has

demonstrated, he is clearly legendary or “at most… a historical

character to whom layers of legend have accrued” (Foley 1998:161). So

taken was Parry with the analogy between Homer and Huso that before his

death he planned a series of articles entitled “Homer and Huso” which

Lord completed based on Parry’s abstracts and notes.

The second singer highlighted in the essay is the one whose picture would grace the cover of

The Singer of Tales, that is to say, Avdo Međedović.

The Singer of Tales,

which publishes the results of Parry and Lord’s investigation of the

South Slavic song tradition and applies them to the Homeric

Iliad and

Odyssey,

was Lord’s fulfillment of Parry’s own plan to write a book of that

title. The singer referred to in the title is of course generic, because

much of what was groundbreaking about Parry and Lord’s work was their

demonstration of the system in which traditional oral poetry is

composed, a system in which many generations of singers participate. But

Lord’s essay makes clear (as does, to a lesser extent,

The Singer of Tales)

that there is also a particular singer behind the title that Parry and

later Lord used to denote their work. That singer is simultaneously Avdo

and Homer himself.

Just as Ćor Huso embodied for Parry the Yugoslav traditional singer,

Avdo was for Lord on a practical level a living, breathing example of a

supremely talented oral poet to whom Homer could be compared. Lord’s

Singer of Tales

is remarkable for its straightforward expostion of the practical

workings of the traditional system in which poets like Avdo composed

their songs; it is no surprise therefore that he found a great deal of

power in the concrete example that Avdo provided. Avdo dictated songs,

was recorded on disk, and was even captured on a very early form of

video called “kinescope.” After their initial encounter in the 1930’s,

Lord found him and recorded him again in the 1950’s. He was in many ways

the test case for Lord’s theories about the South Slavic (and by

extension the Homeric) poetic system.

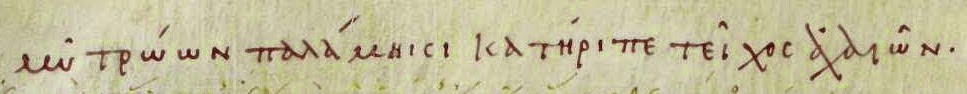

The photograph of Avdo that was featured on the cover of

The Singer of Tales

was one that Lord had taken on his first trip to Yugoslavia and was

included among the images that were to accompany his unpublished essay

(see image above). The caption reads: “Avdo Medjedovitch, peasant

farmer, is the finest singer the expedition encountered. His poems

reached as many as 15,000 lines. A veritable Yugoslav Homer!”

Here is Lord’s fuller description of Avdo in the essay:

"Lying on the bench not far from us was a Turk smoking a

cigarette in an antique silver “cigárluk” (cigarette holder). He was a

tall, lean and impressive person. At a break in our conversation he

joined in. He knew of singers. The best, he said, was a certain Avdo

Medjédovitch, a peasant farmer who lived an hour way. How old is he?

Sixty, sixty-five. Does he know how to read or write? Nézna, bráte! (No,

brother!) And so we went for him… Finally Avdo came, and he sang for us

old Salih’s favorite of the taking of Bagdad in the days of Sultan

Selim. We listened with increasing interest to this short homely farmer,

whose throat was disfigured by a large goiter. He sat cross-legged on

the bench, sawing the gusle, swaying in rhythm with the music. He sang

very fast, sometimes deserting the melody, and while the bow went

lightly back and forth over the string, he recited the verses at top

speed. A crowd gathered. A card game, played by some of the modern young

men of the town, noisily kept on, but was finally broken up. The next

few days were a revelation. Avdo’s songs were longer and finer than any

we had heard before. He could prolong one for days, and some of them

reached fifteen or sixteen thousand lines. Other singers came, but none

could equal Avdo, our Yugoslav Homer."

In these excerpts I think we can see how important Avdo was for Lord’s

earliest conception of Homer as oral poet. Whereas Parry’s never

completed articles comparing the South Slavic and Homeric traditions

focused on the hazy figure of Ćor Huso, Lord, when invited to give a

lecture on

La poesia epica e la sua formazione, entitled his talk

“Tradition and the Oral Poet: Homer, Huso, and Avdo Medjedović.”(See

Lord 1970.) As early as his 1948 article, “Homer, Parry, and Huso,” Lord

links Avdo directly with Parry’s Huso: “During the summer of 1935,

while collecting at Bijelo Polje, Parry came across a singer named Avdo

Međedović, one of those who had heard Ćor Huso in his youth, whose

powers of invention and story-telling were far above the ordinary.”

Lord’s

comments about Avdo, especially in these earliest descriptions of him,

focus on his excellence as a composer (despite the weakness of his

voice), his superiority to other poets, and the length of his songs. It

is not insignificant that in his unpublished essay Lord misestimates the

length of Avdo’s song at 15,000 to 16,000 verses, the approximate

length of the

Iliad, whereas in fact the longest song that Avdo

recorded was 13,331 verses long. By 1948 Lord was careful to report the

accurate total of Avdo’s verses, but he was also careful to point out

how extraordinary the length of Avdo’s songs were in comparison with his

fellow singers, whose songs averaged only a few hundred lines. Clearly

it was Lord’s first impression that Avdo provided the answer to the

still hotly debated Homeric Question.

It would be

easy to criticize Lord's youthful essay, and few people would find

it necessary to do so. And even if we jump forward, decades later, it

seems obvious that Lord conceived of the paradigm of a dictating oral

poet Homer because he was imagining him in Avdo’s image. The technology

used to record Avdo was cutting edge at that time, and Lord would never

have been so anachronistic as to suggest that Homer was recorded on

audio disk. But to assume the technologies required for writing (pen,

ink, loose or bound sheets of readily available paper, skilled scribes,

etc) for “Homer’s time” is an equally anachronistic projection. As much

as Lord’s work is responsible for the paradigm shift in Homeric studies

that has allowed many scholars to abandon the Homer as original genius

genre of criticism, he himself had his blind spots on this crucial

point. Lord could have his Homer and his oral tradition too.

Few people seem to be aware, however, that Lord all but retracted his dictation thesis in his 1991 collection of essays,

Epic Singers and Oral Tradition. There, together with the 1953 article, he included an addendum, from which I quote here:

"As I reconsidered very recently the stylization of a passage from Salih

Ugljanin’s “Song of Bagdad” that was found in a dictated version but not

in two sung texts, I was suddenly aware of the experience of listening

to Salih dictate… the pause interrupted neither Salih’s thought nor his

syntax… One might think that dictating gave Salih the leisure to plan

his words and their placing in the line, that the parallelism was due to

his careful thinking out of the structure. First of all, however,

dictating is not a leisurely process… I might add that not all singers

can dictate successfully. As I have said elsewhere, some singers can

never be happy without the gusle accompaniment to set the rhythm of the

singing performance."

Lord himself as far as I am aware never, in print, discussed the

implications of this important revsion of his 1953 argument. (Lord died

in the same year that

Epic Singers and Oral Tradition was published.) But it is also true that Lord never speculated about the historical circumstances under which the

Iliad and

Odyssey

might have been dictated. For Lord, the question of the text fixation

of the Homeric poems was not essential; rather he was concerned with the

dynamic process, that is to say their on-going recomposition in

performance.

Parry, on the other hand, did not get the chance to

rethink his earlier work, or to conduct further fieldwork or spend

decades studying the the South Slavic tradition and the Homeric poems as

Lord did. His early writings on the economy of Homeric diction are a

brilliant first step towards an entirely new way of conceiving of the

composition of the Homeric poems, but they are only the beginning. Like

Kuhn or Darwin, Parry's work has been assailed by many as mistaken in

this or that particular, or not sufficiently thorough so as to have

worked out all aspects of the system it seeks to describe in detail. As Mary

Ebbott and I discuss in our recent book,

Iliad 10 and the Poetics of Ambush,

much scholarship has been devoted to refining Parry’s initial findings

about the economy of Homeric diction and the nature of the Homeric

formula. There is strong resistance among those who feel that Parry’s

work somehow minimizes the artistry of the poems or that the principles

he outlined restrict the creativity of poets composing in this medium.

Thus even those who accept Parry’s findings often seek to amend

significant aspects of his arguments. We feel that the scope of Parry’s

and Lord’s insights has been ignored, misread or misrepresented, or

dismissed too quickly. Some (though certainly not all) efforts to revise

Parry and Lord are built on a misunderstanding of the principles they

documented in their fieldwork and a lack of awareness of, or at least

appreciation for, the kind of meaning made possible by an oral poetic

tradition. That is not to say, however, that our approach and

interpretations in our book have not also greatly benefited from the

work of scholars who have sought to better understand such essential

concepts as the Homeric formula and the complex relationship between

orality and literacy in ancient Greece. There is, however, a significant

difference between scholarship that expands the central insights of

Parry and Lord’s work, even while modifying certain notions or

definitions, and scholarship that sets out to “prove” Parry (more often

than Lord) “wrong” in order to conclude, usually with no further

justification, that Homer wrote, or somehow “broke free” of the oral

tradition of these epics.

These criticisms, like those

cited by Dr. Lienhard against Kuhn and Darwin, seem to me to react to

Parry as if he had "written the last word on the subject, not the

first." As Dr. Lienhard concludes at the end of the episode:

Kuhn, White, and Darwin are fine reminders that

nothing is finished in its first incarnation. Did

the Wright Brothers get it wrong because they put

the tail in front? Was Edison wrong to record sound

on a wax cylinder instead of a CD? I suppose if we

need only to be absolutely right we'll shy away

from any of our important progenitors. But, if we

want to see creative change in full flower, we have

to go to the delicious flawed beginnings.

Bibliography

Lord, A. B. 1936. “Homer and Huso I: The Singer’s Rests in Greek and South Slavic Heroic Song.

Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 67:106–113.

–––. 1938. “Homer and Huso II: Narrative Inconsistencies in Homer and Oral Poetry.”

Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 69:439–445.

–––. 1948a. “Homer and Huso III: Enjambement in Greek and South Slavic Heroic Song.

Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 79:113–124.

–––. 1948b. “Homer, Parry, and Huso.”

American Journal of Archaeology 52:34–44.

–––. 1953. “Homer’s Originality: Oral Dictated Texts.”

Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 94:124–34.

–––. 1960/2000.

The Singer of Tales. Cambridge, Mass. 2nd ed., ed. S. Mitchell and G. Nagy.

–––. 1970. “Tradition and the Oral Poet: Homer, Huso, and Avdo Medjedovic.”

Atti del Convegno Internazionale sul Tema: La Poesia Epica e la sua Formazione (eds. E. Cerulli et al.) 13–28. Rome.

–––. 1991.

Epic Singers and Oral Tradition. Ithaca, N.Y.

–––. 1995.

The Singer Resumes the Tale. Ithaca, N.Y.

Parry, A., ed. 1971.

The Making of Homeric Verse: The Collected Papers of Milman Parry. Oxford.

Parry, M. 1928.

L’épithète traditionelle dans Homère: essai sur un problème de style homérique. Paris. [Repr. and trans. in A. Parry 1971:1–190.]