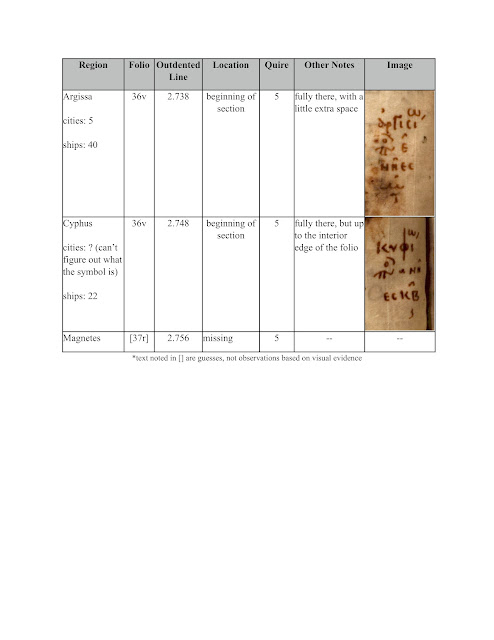

| |

| Athena wearing Zeus's aegis, one of the topics of this scholion |

Among the many potentially befuddling characteristics of the Venetus A manuscript, one thing that is usually fairly straightforward is the connection made to the Iliad text by a scholion’s lemma, an excerpted word or phrase from the Iliad text at the beginning of a scholion which cues the reader as to what lines the scholion will be commenting on. While some scholia have no explicit lemma, these scholia usually indicate clearly what Iliad lines are being commented on based on their content. When a scholion’s lemma has no clear connection to the Iliad text, however, editors are thrown for a loop.

We find such a case at the beginning of Iliad 15, after a newly awakened Zeus sends Iris to order Poseidon to stop his assault on the Trojans. Chafing against the assumed supremacy of his brother, Poseidon angrily reminds Iris that, being a son of Kronos, he has equal authority over the actions of the battlefield as Zeus. Still, Poseidon yields and Zeus then orders Apollo to rouse Hector to arms.

The lemma in question begins the third main scholion on folio 194 verso of the Venetus A.

| Detail of Venetus A 194v: see zoomable version here |

Κρόνος χρησμὸν λαβὼν:This string of words does not appear anywhere on the page. Discrepancy between a lemma and text does happen elsewhere in the Venetus A. Often the differing words in the lemmata actually suggest an apparent multiformity. However, for a lemma to differ so greatly that the discrepancy goes beyond spelling differences or word order is certainly unusual. The Holy Cross team examined the content of the scholion to see if any explanation of multiformity existed, but no such discussion followed:

ὅτι ὀ ΐδιος αὐτὸν τῆς βασιλείας μεταστήσει υἱὸς, τὰ γεννώμενα κατέπινεν Ῥέα δὲ τεκοῦσα Δία, Κρόνῳ μὲν αὐτοῦ λίθον σπαργανώσασα ἔδωκε καταπιεῖν· τὸ δὲ παιδίον εἰς Κρήτην διακομίσασα, ἔδωκε τρέφειν Θέμοδι καὶ Ἀμαλθίᾳ ἡ ἢν αἴξ, ταύτην οἱ Τιτᾶνες ὁποτ ἂν ἐθεάσαντο ἐφοβοῦντο· αὕτη δὲ τοὺς αὑτῆς μαζοὺς ὑπέχουσα ἔτρεφε τὸ παιδίον. αὐξηθεὶς δὲ ὁ Ζεὺς μετέστησε τῆς βασιλείας τὸν πατέρα. πολεμούντων δὲ αὐτὸν τῶν Τιτάνων, Θέμις συνεβούλευσε, τῷ τῆς Ἀμαλθίας δέρματι σκεπαστηρίῳ χρήσασθαι εἶναι γὰρ αὐτὴν ἀεί φόβητρον, πεισθεὶς δὲ ὁ Ζεῦς ἐποίησεν καὶ τοὺς Τιτᾶνας ἐνίκησεν· ἐντεῦθεν αὐτὸν φησὶν αἰγήοχον προσαγορευθῆναιSo not only does the scholion concerning Zeus’s upbringing shed no light on the multiformity of the text, but the scholion’s first word, ὅτι, only confuses matters further. ὅτι is typically used at the beginning of scholia to correlate with Aristarchean critical marks, such that they mean, “[the critical mark was placed there] because.” So not only does the lemma not exist, but the scholion supposedly corresponds with some Aristarchean critical mark that also does not exist, and the content is not typical of the kind of editorial comments Aristarchus makes, either.

ὅτι [Because] his own son will remove him [Kronos] from his dominion, he [Kronos] gulped down his begotten children. But Rhea, after giving birth to Zeus, wrapped a stone in swaddling clothes and then gave it to Kronos to devour. As for the child, she sent him to Crete to be raised by Themis and Amalthia, who was a goat and one whom, whenever the Titans laid eyes on her, was feared. Nursing him at her breast Amalthia raised the child, and once he had grown Zeus stripped his father of his kingdom. But when the Titans were making war with him, Themis advised him to make use of Amalthia’s hide as a shield. For she advised that Amalthia was always terrifying. Persuaded Zeus did so and conquered the Titans. For this reason he says that he was addressed as “aegis-bearing.”

Our team at Holy Cross was not the first editorial team to struggle with this scholion. Both Erbse and Dindorf recognized the peculiarity of the scholion, and having analyzed the content, concluded that the scribe had made a mistake in placing this scholion here and decided that he meant to comment on line 229 of book 15:

ἀλλὰ σύ γ᾽ ἐν χείρεσσι λάβ᾽ αἰγίδα θυσσανόεσσαν, (15.229)On the one hand this conclusion makes some sense. That line contains mention of the aegis, it contains some form of the word λαμβάνω, a word from the lemma, and the name Kronos, another word in the lemma, appears just four lines above. While it would still be a stretch, it is perhaps understandable how there might exist some multiform which included our given lemma in the around this part of the text. The problem with this interpretation is that line 15.229 appears on folio 195v, two folios later from where the scholion actually appears. Such a “mistake” seems extremely unlikely for the scribe of the Venetus A who, on every other account, scrupulously connects scholia with their textual counterparts on the same physical page.

Assuming that the scribe did not make that egregious error, some other explanation is required. Our Holy Cross team decided to look at the surrounding scholia to look for positioning clues. The main scholia are ordered sequentially with the line they comment on. So a scholion on line 2 will succeed a scholion on line 1 while immediately preceding a scholion on line 3. In this case, our scholion of interest is sandwiched by two grammatical scholia on line 15.187. Since a single line can have multiple scholia, it is only logical that our scholion in question must also comment on the line. An examination of the line 15.187 reveals that such a conclusion is not too far-fetched:

τρεῖς γάρ τ᾽ ἐκ Κρόνου εἰμὲν ἀδελφεοὶ οὓς τέκετο Ῥέα (15.187)While the text and lemma do not match, the poetic line is connected to the scholion’s content: namely, it is about one child of Kronos and Rhea. It seems safe to say that the scholion is simply providing an expanded mythological background to the story of Kronos’s children.

How then must we take this ghost lemma? It has every indication of being a lemma in that it is written in the same lettering that is used for lemmata and is set apart from the rest of the scholion by a colon. The solution then is to concede that the scribe did make a mistake or, at least, that some scribe at some point in the manuscript tradition made a mistake. One must concede that Κρόνος χρησμὸν λαβὼν is not a lemma after all, but merely the beginning of the scholion mistakenly written as a lemma. If one removes the colon after λαβὼν, first sentence of the scholion reads:

Κρόνος χρησμὸν λαβὼν ὅτι ὀ ΐδιος αὐτὸν τῆς βασιλείας μεταστήσει υἱὸς, τὰ γεννώμενα κατέπινενNo longer does one have to infer from context who the father is whose dominion is being stripped away, nor does one have to supply a subject for κατέπινεν. Both cases are elucidated by the clearly nominative form Κρόνος. Most importantly the ὅτι which likely threw off Erbse and Dindorf given its usual formulaic structure in the scholia serves instead here as just a marker of indirect speech, “that,” rather than an indicator of critical marks. And with that conclusion our diplomatic edition was able to not only keep true to the manuscript’s layout, unlike Erbse and Dindorf, but also make sense of something that had baffled some of the brightest Homeric scholars.

Kronos, having received an oracle that his own son will remove him from his dominion, gulped down his begotten children.